Iranian New Wave cinema will be discussed at 72nd Melbourne International Film Festival

Melbourne International Film Festival will discuss Iranian New Wave cinema.

MojNews-Melbourne International Film Festival will discuss Iranian New Wave cinema.

The 72nd Melbourne International Film Festival (MIFF), to be held from August 8 to 25 in Australia, has dedicated a special section to the Iranian classic films.

Titled “Iranian New Wave: 1962–79,” the program includes short and feature films as well as animations made by well-known Iranian directors, who had a great influence on the film industry of the country, ISNA reported.

Iranian Cinema Before the Revolution, 1925-1979, a landmark retrospective held last year at The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, was an eye-opener that traced a national cinema still largely unknown to a wide international audience.

Thanks to the availability of new restorations and rare archival film prints, an immensely creative period was revisited in splendid detail, revealing the roots of a rich and visionary cinematic tradition. While the New York program featured over five decades of Iranian cinema encompassing the avant-garde and the popular, this selection for the Melbourne International Film Festival focuses on works associated with Cinema-ye Motafavet, or the Iranian New Wave.

Cinema-ye Motafavet was a grassroots movement in Iranian documentary, fiction, and animation cinema during the 1960s and 70s that, thanks to close collaboration among filmmakers and talents from the worlds of literature, music, visual arts, and theatre, achieved a glorious coherence, unique in the cinema of the Middle East. Dealing with themes of alienation, anxiety, and repression, Cinema-ye Motafavet revealed the contradictions of Iranian life with haunting clarity.

This program starts with the unparalleled story of a private film company, the Golestan Film Unit, which, in between producing industrial documentaries, supported the production of the first new wave documentary masterpiece, “The House is Black” (1962), by poet Forough Farrokhzad, as well as the movement’s first fiction milestone, Ebrahim Golestan’s “Brick and Mirror” (1964). Farrokhzad and Golestan also collaborated on “A Fire” (1961), the first in a series of commissioned films in Iran that wryly subverted the notion of commissioned cinema.

“The House Is Black,” set in a leper colony in north-west Iran, is the only film directed by Farrokhzad before her premature death at 32. It uses her poetry to discuss seclusion and pain and is now considered one of the greatest documentaries ever made.

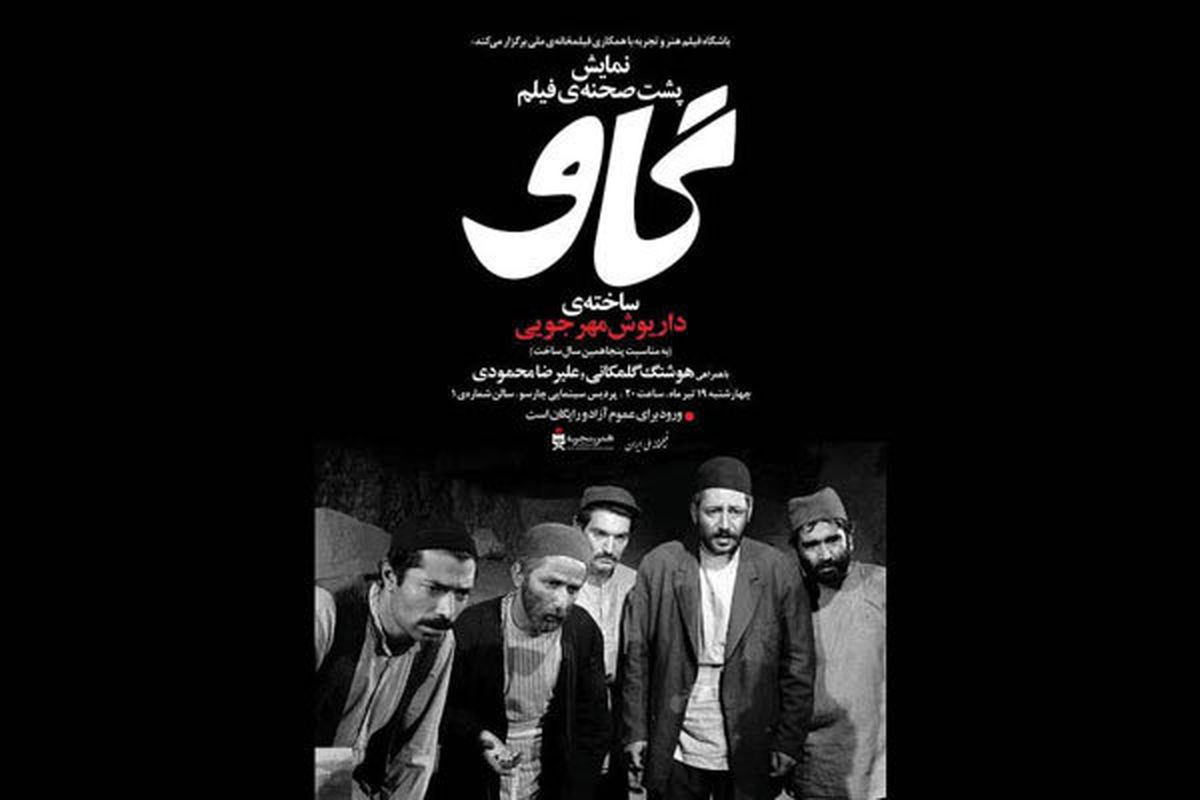

The increasing popularity of Iranian cinema was not overlooked by the state, which began to support it through institutions such as the National Television, the Center for Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults (Kanoon), and the Ministry of Culture. It was in that context that Dariush Mehrjui’s “The Cow” (1969) – a major hit at both Cannes and Venice festivals – was born and stunned audiences, followed by Sohrab Shahid Saless’s brilliantly austere “A Simple Event” (1973).

Made clandestinely with little money and a skeleton crew, Sohrab Shahid Saless’s 1973 debut feature, “A Simple Event,” is a quietly, mysteriously simmering masterpiece.

It follows a few days in the life of a young boy living beside the Caspian Sea. Remarkably, Shahid Saless inspires viewers to respond emotionally to characters seemingly devoid of any feeling themselves; the simple event of the film’s title refers, perhaps, to a sudden and tragic death, or perhaps instead to the mundane sounds of dogs barking and crickets chirping.

“The Cow,” the ۱۹۶۹ milestone of the Iranian New Wave portrays, with heartbreaking intensity, the themes of solitude and obsession in the story of a poor villager whose only source of joy and livelihood is his cow.

When the cow of a villager (unforgettably played by Ezzatolah Entezami) is mysteriously killed one night, the metamorphosis begins. Based on short stories by psychiatrist Gholam-Hossein Sa’edi, “The Cow” was smuggled to the Venice Film Festival in defiance of an export ban, where it was almost immediately and internationally recognized as a masterpiece.

The film came under the spotlight more than a decade later, when Imam Khomeini hailed it as an example of “good cinema”, as opposed to the many “corrupting films” of the Pahlavi era.

In an Iranian paradox, while the state-supported modernist cinema, it also held it back through censorship. “The Cow” and the short gem “The Night It Rained” (۱۹۶۷), by Karman Shirdel, fell victim to this suppression. Similarly affected were films from a very popular middle-of-the-road movement that stood between the New Wave and the mainstream, including “The Deer” (۱۹۷۴), the brevity of which bordered on militant cinema. Banned after one screening, the censor forced the film’s director Masoud Kimiai to shoot a new ending. Both endings will be shown in this program.

Through the lens of cinema, years before the revolution swept across the country, discontent and angst were presaged in films such as “Tranquility in the Presence of Others” (Nasser Taghavi, ۱۹۶۹), “The Stranger and the Fog” (Bahram Beyzai, ۱۹۷۴), “Dead End” (Parviz Sayyad, ۱۹۷۷) and “The Tall Shadows of Wind” (Bahman Farmanara, ۱۹۷۹).

The “Iranian New Wave: ۱۹۶۲–۷۹” section at the upcoming MIFF also comprises two sub-sections namely “Kanoon: From Didactic to Poetic, ۱۹۷۴-۷۷” and “Golden Age of Iranian Animation, ۱۹۶۵-۷۷”.

A suite of films produced by Kanoon, the celebrated agency that brought culture and literacy to children and young adults in Iran, will be presented at the “Kanoon: From Didactic to Poetic, ۱۹۷۴-۷۷”.

The series starts with Abbas Kiarostami’s short films about education and educators. Originally titled “Teachers: A Few Sketches and Memories” and commissioned by the Ministry of Education, “Tribute to the Teachers” is a series of nuanced, touching interviews with schoolteachers. “Two Solutions for One Problem” is a charming slapstick about tolerance and civility. In “Solution No. ۱,” a driver has to deal with a flat tire on top of Alborz Mountain.

Amir Naderi, who collaborated with Kiarostami as a screenwriter, made his second Kanoon film, “Waiting,” (۱۹۷۴) about a southern boy who falls for a girl, though he’s only seen her hands. Showing Naderi at the peak of his purely visual storytelling, this nearly silent film shows how the former photographer used his keen visual aesthetic to tell impressionistic stories of repression and rebellion.

The “Golden Age of Iranian Animation, ۱۹۶۵-۷۷” is a showcase of Iranian animation in a variety of styles and themes, from the early efforts of Western-educated filmmakers like Nosrat Karimi to award-winning shorts produced by Kanoon.

This program reveals two divergent aesthetic tendencies in this period of the ۱۹۷۰s: one inspired by medieval Persian miniature painting and other classic art forms, evident in the work of Karimi (who studied at FAMU in Prague) and Ali Akbar Sadeghi; and the other projecting a more modernist spirit, as seen in the experimental figurative work of Farshid Mesghali.

Films in this package include “Malek Jamshid” (Nosrat Karimi, ۱۹۶۵), “Grey City” (Farshid Mesghali, ۱۹۷۲), “Malek Black Bird” (Morteza Momayez, ۱۹۷۳), “Atal Matal” (Norrodin Zarrin-Kelk, ۱۹۷۴), “Rook” (Ali Akbar Sadeghi, ۱۹۷۴), “I Am the One Who” (Ali Akbar Sadeghi, ۱۹۷۴), “The Mad, Mad, Mad World” (Norrodin Zarrin-Kelk, ۱۹۷۵), “Malak Khorshid (Ali Akbar Sadeghi, ۱۹۷۵), and “Better, Comfier” (Farshid Mesghali, ۱۹۷۷).

Established in ۱۹۵۲, the Melbourne International Film Festival is one of the oldest film festivals in the world. The festival offers several sections dedicated to international films.

Add Comment